The “Living Forest” is how Haliburton Forest has been appropriately and frequently described by many of its visitors and guests over the years. While commonly forests appear to us as static and void of action or development, Haliburton Forest, with all of its attractions and uses, clearly breaks this mold. The term was therefore chosen as title for a book about Haliburton Forest. Today it has been published in two parts, the second part has been published in 2012.

Frequent visitors to Haliburton Forest over the past years will be aware of the original version of “The Living Forest”. It was one of Haliburton Forest’s Millennium projects in 2000, and covers an introduction to Haliburton Forest, its history, ecology and operation at that time. The text was provided by Brent Wootten and myself, and the book was richly illustrated by David Alexander Risk.

Frequent visitors to Haliburton Forest over the past years will be aware of the original version of “The Living Forest”. It was one of Haliburton Forest’s Millennium projects in 2000, and covers an introduction to Haliburton Forest, its history, ecology and operation at that time. The text was provided by Brent Wootten and myself, and the book was richly illustrated by David Alexander Risk.

The latter is a renowned artist who had spent the previous two years at Haliburton Forest, gathering studies and impressions, on which his works are based. But the real feature of that book, we feel, is the fact that it is exclusively printed on paper generated from trees grown at Haliburton Forest. For this Haliburton Forest used the stringent chain of custody process, which was part of the FSC certification it achieved in 1998. It is therefore probable that trees,  which feature in one or several of David Risk’s illustrations subsequently were felled and their fiber served to hold the print that makes up the book. We believe this is the first and only time this has happened: to have a book printed on trees of a forest that the actual book is about.

which feature in one or several of David Risk’s illustrations subsequently were felled and their fiber served to hold the print that makes up the book. We believe this is the first and only time this has happened: to have a book printed on trees of a forest that the actual book is about.

The Living Forest, Part Two follows the path blazed by the initial Living Forest volume. It served to contribute to our celebration of Haliburton Forest’s 50th corporate birthday. And true to its title sufficient change has occurred at Haliburton Forest since the publishing of the first part of the Living Forest, that an update seemed appropriate after 12 years. Maintaining consistency and building on the success of the first book, which sold over 4,000 times, we kept to the same format, size and make-up. Only the cover was changed, incorporating illustration items of some of the stories in the book is touching on. David Risk came on board once again and, as artist in residence at Haliburton Forest in 2011 and 2012, created a dazzling array of numerous, high quality illustrations to accompany the text. The body of the text, which was written again by myself, consists of 4 distinctly different chapters.

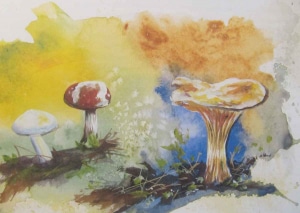

The first deals with “Life in the Forest” and reflects on many of the environmental and ecological changes we observed and insights we gained over the past dozen years. It describes in detail some of the research conducted at Haliburton Forest, but also contains personal reflections on events and changes. It also incorporates some of the new and interesting operations, such as the apiary (beekeeping) or the husbandry of various fungi.

The first deals with “Life in the Forest” and reflects on many of the environmental and ecological changes we observed and insights we gained over the past dozen years. It describes in detail some of the research conducted at Haliburton Forest, but also contains personal reflections on events and changes. It also incorporates some of the new and interesting operations, such as the apiary (beekeeping) or the husbandry of various fungi.

The second chapter introduces the reader to the threat of alien invaders, encroaching on our forests, wetlands and lakes. Brought about by global trade, many organisms, from fungi to insects and plants to fish are posing lethal threats to many components of our environments, we still take for granted. Be it tree species like beech or ash, fish such as our native trout species or even large mammals like moose are under threat from alien, non-native organisms. The fact that this threat is not only real, but poses one of the biggest dangers to our environment as a whole is paid tribute to by providing it space in an entire chapter.

The third chapter deals with Haliburton Forest’s struggle with bureaucracy. Operating in the field of resource management, where commonly in Canada “The Crown” by sheer ownership of over 90% of the land, has a monopoly, Haliburton Forest is an “odd duck”. This presents many challenges for our operation, but also insights, which are hard to gain from outside the system. Not helping Haliburton Forest’s government relations is its innovative nature, which often places it in the path of the public steamroller, which only knows one speed and one direction. The best example for this is the story of Haliburton Forest’s submarine, which is also dwelled upon in this chapter.

The third chapter deals with Haliburton Forest’s struggle with bureaucracy. Operating in the field of resource management, where commonly in Canada “The Crown” by sheer ownership of over 90% of the land, has a monopoly, Haliburton Forest is an “odd duck”. This presents many challenges for our operation, but also insights, which are hard to gain from outside the system. Not helping Haliburton Forest’s government relations is its innovative nature, which often places it in the path of the public steamroller, which only knows one speed and one direction. The best example for this is the story of Haliburton Forest’s submarine, which is also dwelled upon in this chapter.

After two chapters of doom and gloom, the concluding section of the book provides a positive outlook, dealing with Haliburton Forest’s biochar story. It throws a wide net, bringing together some of my management philosophies and family history with an outlook into our carbon crazed future. And here biochar becomes more a concept than it is a substance.

The Living Forest, Part Two is above all a description of Haliburton Forest’s present state. The foreword by my good friend Gary Bull, forestry professor at UBC, puts it best when he states “… it is not all about business; it is about working with nature’s boundaries and with people“. In the first printing, this foreword was incorrectly headlined “forward”, which is not that unfitting after all …

With what we have “brewing” at Haliburton Forest at the moment, I am sure, within the next decade it will be necessary to update The Living Forest with a part three. For this the present book sets the stage, raising expectations, hope and thrusting a glance into an interesting, changing future.